Recommendations for the Reading Stage in Syllables and Affixes Stage

Stages of language conquering in children

In about all cases, children's linguistic communication development follows a predictable sequence. However, at that place is a great deal of variation in the age at which children reach a given milestone. Furthermore, each kid's development is unremarkably characterized by gradual conquering of detail abilities: thus "correct" use of English language verbal inflection will emerge over a period of a year or more, starting from a stage where vebal inflections are always left out, and ending in a stage where they are well-nigh always used correctly.

There are also many different ways to characterize the developmental sequence. On the production side, i way to name the stages is as follows, focusing primarily on the unfolding of lexical and syntactic cognition:

| Phase | Typical historic period | Clarification |

| Babbling | 6-8 months | Repetitive CV patterns |

| One-discussion stage (better one-morpheme or i-unit) or holophrastic stage | nine-xviii months | Single open-class words or word stems |

| Two-word phase | 18-24 months | "mini-sentences" with uncomplicated semantic relations |

| Telegraphic phase or early multiword stage (amend multi-morpheme) | 24-30 months | "Telegraphic" sentence structures of lexical rather than functional or grammatical morphemes |

| Later multiword stage | 30+ months | Grammatical or functional structures emerge |

Vocalizations in the first year of life

At birth, the baby vocal tract is in some ways more than like that of an ape than that of an developed human. Compare the diagram of the infant vocal tract shown on the left to diagrams of adult human and ape.

At birth, the baby vocal tract is in some ways more than like that of an ape than that of an developed human. Compare the diagram of the infant vocal tract shown on the left to diagrams of adult human and ape.

In particular, the tip of the velum reaches or overlaps with the tip of the epiglottis. As the infant grows, the tract gradually reshapes itself in the developed pattern.

During the showtime 2 months of life, infant vocalizations are mainly expressions of discomfort (crying and fussing), along with sounds produced as a past-product of reflexive or vegetative deportment such as coughing, sucking, swallowing and burping. There are some nonreflexive, nondistress sounds produced with a lowered velum and a closed or nearly airtight oral cavity, giving the impression of a syllabic nasal or a nasalized vowel.

During the menstruum from about ii-four months, infants begin making "condolement sounds", typically in response to pleasurable interaction with a caregiver. The primeval condolement sounds may be grunts or sighs, with later versions beingness more vowel-similar "coos". The song tract is held in a fixed position. Initially comfort sounds are brief and produced in isolation, but later announced in serial separated by glottal stops. Laughter appears around 4 months.

During the period from 4-7 months, infants typically engage in "song play", manipulating pitch (to produce "squeals" and "growls"), loudness (producing "yells"), and also manipulating tract closures to produce friction noises, nasal murmurs, "raspberries" and "snorts".

At nigh vii months, "canonical babbling" appears: infants get-go to make extended sounds that are chopped up rhythmically past oral articulations into syllable-similar sequences, opening and closing their jaws, lips and tongue. The range of sounds produced are heard as stop-like and glide-like. Fricatives, affricates and liquids are more than rarely heard, and clusters are fifty-fifty rarer. Vowels tend to be low and open, at least in the offset.

Repeated sequences are often produced, such equally [bababa] or [nanana], too equally "variegated" sequences in which the characteristics of the consonant-similar articulations are varied. The variegated sequences are initially rare and become more mutual afterwards.

Both vocal play and babbling are produced more than oft in interactions with caregivers, but infants will also produce them when they are lonely.

No other animate being does annihilation like babbling. Information technology has ofttimes been hypothesized that vocal play and babbling take the office of "practicing" voice communication-like gestures, helping the infant to gain control of the motor systems involved, and to learn the acoustical consequences of different gestures.

One give-and-take (holophrastic) phase

At near 10 months, infants outset to utter recognizable words. Some word-like vocalizations that do non correlate well with words in the local language may consistently be used past particular infants to limited particular emotional states: one infant is reported to have used ![]() to express pleasure, and another is said to have used

to express pleasure, and another is said to have used ![]() to express "distress or discomfort". For the nearly part, recognizable words are used in a context that seems to involve naming: "duck" while the child hits a toy duck off the edge of the bath; "sweep" while the child sweeps with a broom; "machine" while the kid looks out of the living room window at cars moving on the street below; "papa" when the kid hears the doorbell.

to express "distress or discomfort". For the nearly part, recognizable words are used in a context that seems to involve naming: "duck" while the child hits a toy duck off the edge of the bath; "sweep" while the child sweeps with a broom; "machine" while the kid looks out of the living room window at cars moving on the street below; "papa" when the kid hears the doorbell.

Young children oft use words in ways that are too narrow or too broad: "bottle" used only for plastic bottles; "teddy" used only for a detail acquit; "dog" used for lambs, cats, and cows as well every bit dogs; "kick" used for pushing and for wing-flapping as well as for kicking. These underextensions and overextensions develop and change over fourth dimension in an private child's usage.

Perception vs. product

Clever experiments have shown that about infants can give evidence (for instance, by gaze direction) of understanding some words at the age of iv-nine months, often even before babbling begins. In fact, the development of phonological abilities begins even before. Newborns tin distinguish spoken communication from non-speech, and can also distinguish among speech sounds (e.g. [t] vs. [d] or [t] vs. [chiliad]); inside a couple of months of nativity, infants can distinguish oral communication in their native language from speech in other languages.

Early linguistic interaction with mothers, fathers and other caregivers is virtually certainly of import in establishing and consolidating these early abilities, long before the kid is giving any indication of language abilities.

Rate of vocabulary development

In the first, infants add together active vocabulary somewhat gradually. Hither are measures of active vocabulary development in two studies. The Nelson study was based on diaries kept by mothers of all of their children's utterances, while the Fenson study is based on asking mothers to check words on a list to betoken which they recollect their child produces.

| Milestone | Nelson 1973 (18 children) | Fenson 1993 (1,789 children) |

| 10 words | xv months (range 13-19) | thirteen months (range 8-sixteen) |

| 50 words | 20 months (range 14-24) | 17 months (range ten-24) |

| Vocabulary at 24 months | 186 words (range 28-436) | 310 words (range 41-668) |

In that location is often a spurt of vocabulary acquisition during the second year. Early words are acquired at a rate of one-iii per week (equally measured past production diaries); in many cases the charge per unit may of a sudden increment to 8-10 new words per week, after twoscore or so words take been learned. However, some children prove a more steady rate of acquisition during these early on stages. The rate of vocabulary acquisition definitely does accelerate in the third year and across: a plausible estimate would be an average of 10 words a day during pre-schoolhouse and elementary school years.

Sex differences in vocabulary acquisition

Against a groundwork of enormous individual variation, girl babies tend to learn more than words faster than boy babies do; but the deviation disappears over time.

Svetlana Lutchmaya, Simon Businesswoman-Cohen and Peter Raggat ("Foetal testosterone and vocabulary size in xviii- and 24-month infants", Infant Behavior and Development 24:418-424, 2002) establish that in a sample of xviii-month-olds, boys' boilerplate vocabulary size was 41.eight words (range from 0 to 222, standard deviation l.1), while girls' average was 86.eight (range from ii to 318, standard deviation 83.2). By 24 months, the difference had narrowed to a boys' hateful of 196.8 (range 0 to 414, standard divergence 126.eight) vs. a girls' mean of 275.1 (range fifteen to 415, SD=121.6). In other words, the girls' reward in average values had shrunk from 86.8/41.8 = 2.1 to 275.i/196.8 = one.v.

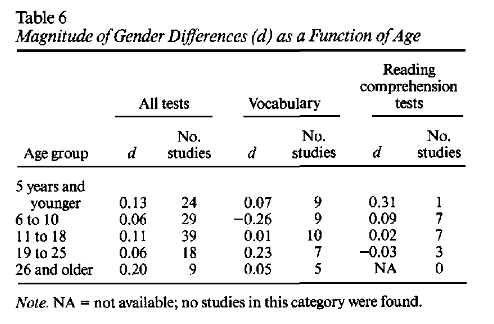

Equally time passes, the difference disappears entirely, and and then emerges again in the contrary direction, with males showing larger boilerplate vocabularies during college years (though again against the background of within-grouping variation that'southward much larger than the across-grouping differences). Here's table vi from Janet Shibley Hyde and Marcia C. Linn, "Gender Differences in Verbal Ability: A Meta-Analysis", Psychological Bulletin, 104:one 53-69 (1988).

Perception vs. product again

Bridegroom (1979) asked mothers to keep a diary indicating not only what words children produced, but what words they gave evidence of understanding. Her results indicate that at the time when children were producing 10 words, they were estimated to understand 60 words; and there was an average gap of 5 months between the fourth dimension when a child understood 50 words and the fourth dimension when (southward)he produced l words.

All of these methods (maternal diaries and checklists) probably tend to underestimate the number of words nearly young children really know something, although they also may overestimate the number of words to which they aspect adult-like meanings.

Combining words: the emergence of syntax

During the second year, word combinations brainstorm to announced. Novel combinations (where nosotros can be sure that the issue is not beingness treated every bit a single word) announced sporadically every bit early on as 14 months. At 18 months, 11% of parents say that their child is often combining words, and 46% say that (s)he is sometimes combining words. By 25 months, almost all children are sometimes combining words, but about twenty% are still not doing and then "oftentimes."

Early multi-unit utterances

In some cases, early on multiple-unit utterances can be seen as concatenations of individual naming actions that might just too have occured lone: "mommy" and "chapeau" might exist combined as "mommy hat"; "shirt" and "moisture" might be combined every bit "shirt wet". All the same, these combinations tend to occur in an order that is appropriate for the language being learned:

- Doggy bark

- Ken water (for "Ken is drinking h2o")

- Striking doggy

Some combinations with sure airtight-class morphemes begin to occur also: "my turn", "in there", etc. However, these are the airtight-form words such every bit pronouns and prepositions that have semantic content in their own right that is not too dissimilar from that of open-course words. The more purely grammatical morphemes -- verbal inflections and verbal auxiliaries, nominal determiners, complementizers etc. -- are typically absent.

Since the earliest multi-unit utterances are almost always two morphemes long -- two beingness the first number after i! -- this menstruum is sometimes called the "two-word stage". Quite soon, notwithstanding, children begin sometimes producing utterances with more than ii elements, and it is not articulate that the period in which well-nigh utterances take either one or two lexical elements should really be treated as a separate stage.

In the early multi-word stage, children who are asked to repeat sentences may just leave out the determiners, modals and exact auxiliaries, verbal inflections, etc., and often pronouns equally well. The aforementioned blueprint tin can be seen in their own spontaneous utterances:

- "I can see a cow" repeated as "Come across moo-cow" (Eve at 25 months)

- "The doggy will bite" repeated as "Doggy bite" (Adam at 28 months)

- Kathryn no similar celery (Kathryn at 22 months)

- Baby doll ride truck (Allison at 22 months)

- Pig say oink (Claire at 25 months)

- Desire lady get chocolate (Daniel at 23 months)

- "Where does Daddy go?" repeated equally "Daddy become?" (Daniel at 23 months)

- "Motorcar going?" to mean "Where is the car going?" (Jem at 21 months)

The blueprint of leaving out most grammatical/functional morphemes is called "telegraphic", and so people also sometimes refer to the early on multi-give-and-take phase every bit the "telegraphic stage".

Acquisition of grammatical elements and the corresponding structures

At about the age of two, children first begin to use grammatical elements. In English, this includes finite auxiliaries ("is", "was"), verbal tense and understanding affixes ("-ed" and '-south'), nominative pronouns ("I", "she"), complementizers ("that", "where"), and determiners ("the", "a"). The process is ordinarily a somewhat gradual one, in which the more than telegraphic patterns alternate with developed or adult-like forms, sometimes in adjacent utterances:

- She'due south gone. Her gone schoolhouse. (Domenico at 24 months)

- He'south boot a beach ball. Her climbing upwards the ladder in that location. (Jem at 24 months).

- I teasing Mummy. I'1000 teasing Mummy. (Holly at 24 months)

- I having this. I'm having 'nana. (Olivia at 27 months).

- I'thousand having this little one. Me'll have that. (Betty at 30 months).

- Mummy haven't finished notwithstanding, has she? (Olivia at 36 months).

Over a twelvemonth to a twelvemonth and a half, sentences get longer, grammatical elements are less often omitted and less often inserted incorrectly, and multiple-clause sentences become commoner.

Perception vs. production over again

Several studies accept shown that children who regularly omit grammatical elements in their speech, nevertheless expect these elements in what they hear from adults, in the sense that their judgement comprehension suffers if the grammatical elements are missing or absent-minded.

Progress backwards

Often morphological inflections include a regular case ("walk/walked", "open/opened") and some irregular or exceptional cases ("become/went", "throw/threw", "hold/held"). In the beginning, such words will be used in their root class. As inflections beginning start being added, both regular and irregular patterns are found. At a certain point, it is common for children to over-generalize the regular case, producing forms like "bringed", "goed"; "foots", "mouses", etc. At this stage, the kid'southward oral communication may actually become less correct by adult standards than it was earlier, because of over-regularization.

This over-regularization, like almost other aspects of children'southward developing grammar, is typically resistant to correction:

CHILD: My teacher holded the baby rabbits and nosotros patted them. ADULT: Did y'all say your instructor held the baby rabbits. Child: Yep. ADULT: What did y'all say she did? Child: She holded the infant rabbits and we patted them. ADULT: Did you say she held them tightly? Child: No, she holded them loosely.

More Information

A good starting point for more information about kid language conquering is the CHILDES web site at CMU, where y'all can discover out virtually downloading the raw materials of child linguistic communication research, and also search a specialized child language bibliography.

A recent article in the NYT Magazine (Paul Tough, "What it takes to make a educatee", xi/26/2006) discusses at length some well-known studies about social-class differences in language acquisition (Betty Hart and Todd Risley, "Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experience of Immature American Children" (1995); Betty Hart, "A Natural History of Early on Language Experience", Topics in Early on Babyhood Special Education, 20(ane), 2000; "The early Catastrophe: the thirty Million Give-and-take Gap", American Educator, 27(1) pp. iv-nine, 2003). The abstract from the 2003 paper:

By age 3, children from privileged families have heard 30 million more words than children from underprivileged families. Longitudinal data on 42 families examined what accounted for enormous differences in rates of vocabulary growth. Children turned out to be like their parents in stature, activity level, vocabulary resources, and language and interaction styles. Follow-upward information indicated that the 3-yr-onetime measures of accomplishment predicted third grade school achievement.

42 is not a very big sample, and there are many other questions to enquire, but this work suggests that we should be concerned most possible lasting effects of cultural differences in children'due south linguistic environment.

Another, more recent, study suggesting the aforementioned conclusion is Martha J. Farah, et al., ("Childhood poverty: Specific associations with neurocognitive evolution", Brain Inquiry 1110(1) 166-174, September 2006). Prof. Farah and her co-workers "administered a bombardment of tasks designed to tax specific neurocognitive systems to healthy low and heart SES [socio-economic status] children screened for medical history and matched for age, gender and ethnicity".

Fig. 1. Upshot sizes, measured in standard deviations of separation betwixt low and centre SES group operation, on the composite measures of the vii dissimilar neurocognitive systems assessed in this study. Black bars stand for outcome sizes for statistically significant effects; grey bars correspond effect sizes for nonsignificant effects.

All the participants in this study were African-American girls between the ages of ten and 13. Equally the graph above indicates, the divergence in performance on the "Language" function of the test battery betwixt middle SES and low SES girls represented an effect size of nigh 0.95.

There were two language-related tasks:

Peabody Moving picture Vocabulary Examination (PPVT)

This is a standardized vocabulary test for children between the ages of 2.v and 18. On each trial, the child hears a give-and-take and must select the corresponding picture from amidst iv choices.

Test of Reception of Grammer (TROG)

In this sentence–picture matching chore designed by Bishop (1982), the kid hears a sentence and must choose the picture, from a set of four, which depicts the sentence. Its lexical–semantic demands are negligible as the vocabulary is uncomplicated and a pre-exam ensures that subjects know the meanings of the small-scale prepare of words that occur in the examination.

This finding is consistent with a lasting event of differences like those in the Hart & Risly study, ,though other explanations are too possible.

Source: https://www.ling.upenn.edu/courses/Fall_2019/ling001/acquisition.html

0 Response to "Recommendations for the Reading Stage in Syllables and Affixes Stage"

Post a Comment